LIFE AS MYTH

![]()

JOURNAL

![]()

JOURNAL 2015

1001 stories

The gift of voice

![]()

AUTUMN 2015

But then face to face

![]()

LIFEWORKS

![]()

ATLAS

![]()

AUTUMN 2015

BUT THEN FACE TO FACE

The madonna of the book. Sandro Boticelli. Museo Poldi Pezzoli. The arrow-like nails and barbed bracelet of the Christ child are later additions.

(left) The six-winged-seraph, also known as Azrael. Mikhail Vrubel. 1904. Russian Museum, St. Petersburg. Azrael, meaning helper of God, is the traditional angel of death, working as an escort between worlds and comforting those in despair. Vrubel was a painter of the Symbolist movement and, in this painting, he depicts Azrael as Psyche, carrying her trademark blade and lantern.

For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.

I Corinthians 13:12 (KJV)

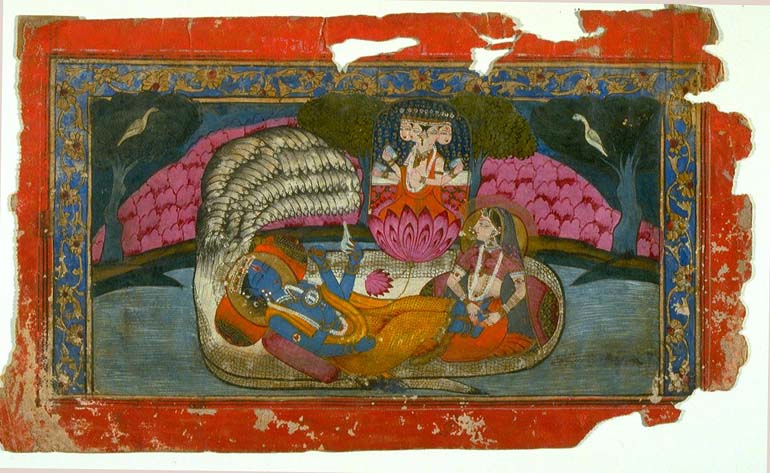

The dream of the world, 19th c. University of Michigan Museum of Art. Gift of Walter M. Spink.

THE POWER OF STORY. . . Kansas is a universe of black asphalt and wheat crops. If you have ever driven across it, you will appreciate how the gift of a story well told made all the difference.

My first encounter with Life of Pi began one June afternoon in 2003 – near where the wet greens of Missouri meet the turbulent golds of the Great Plains. I was on a road trip from Atlanta to Denver, alone except for the audio version of Pi which I had rented at a Cracker Barrel near Clarksville, Tennessee.

Kansas is a universe of black asphalt and wheat crops. If you have ever driven across it, you will appreciate how the gift of a story well told made all the difference. For ten hours Martel’s storytelling held me, black asphalt and wheat crops notwithstanding. What is most remarkable to me about that first experience is how vividly the story has stayed with me. In part, its enduring immediacy arises out of the first person point of view of a sixteen-year-old Hindu-Christian-Muslim but it is more than that. It is the encyclopedic knowledge of animals and their habits that has followed me from Kansas. Annie Dillard was the first writer to do that for me. She described the death march of silk processionaries, the staggering gait of a crippled polyphemus moth, the cannibalistic love rites of praying mantis and scorched those images into my being. Martel, with another voice and another genre, creates the same intimate proximity to the natural world. A dense blue spray of flying fish, the Eden-like meerkats of an algae island, and a starving tiger named Richard Parker now play within my internal landscape. Very few stories affect me that way.

My second encounter with Life of Pi coincided with the publication of the illustrated version. I read the newly illuminated text while waiting in the emergency department of the New York-Presbyterian Hospital. My ten hour journey with Pi from Missouri to Colorado became my ten hour sojourn in the borderland of urban emergency medical care. I completed the book around one in the morning next to the nurse’s station, surrounded by gurneys, chirping cardiac equipment and the remains of a turkey on white bread sandwich. If you have waited for hours in a hospital emergency room, you will appreciate how the gift of a story well told made all the difference, gurneys and chirping equipment notwithstanding.

What these two experiences share is the transformative effect Pi had on my reality. But it does not stop there. As I write now, both the story and the experience of the story continue to evolve for me. Story is a living thing which has the power to transform and to be transformed. This is a truth which is clearer to me now, thanks to a Kansas highway, a hospital waiting room and uninterrupted hours with Life of Pi.