LIFE AS MYTH

![]()

JOURNAL

![]()

JOURNAL 2010

![]()

A vision quest

Finding a guiding light

![]()

SUMMER 2010

Showing the way

The Black Madonna of Częstochowa

![]()

LIFEWORKS

![]()

ATLAS

![]()

SUMMER 2010

SHOWING THE WAY

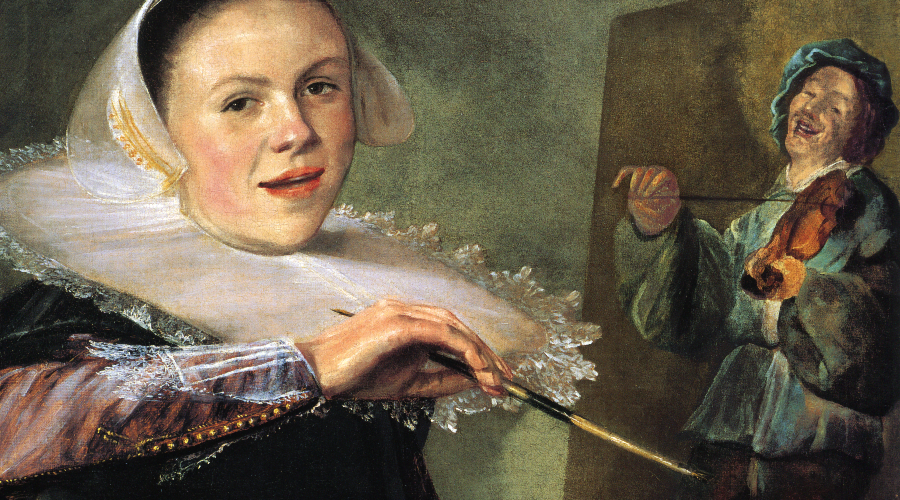

Judith Leyster, self-portrait (detail), 1630. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. In 1633 she was the first woman to join the Haarlem guild. (left) The proposition also known as Man offering money to a young woman, Judith Leyster, 1631. Royal Picture Gallery, Mauritshuis in The Hague. This early painting by Leyster is also one of her finest. Interpretations of the piece vary, with some art critics arguing that Leyster paints against the contemporary convention of the day, depicting a sexual proposition as uninvited and unwelcome.

The Guild of Saint Luke was an organization of European artists within the larger guild system between the 14th and 18th centuries. Taking its name from the apostle credited with painting the first icon of Mary, this group was one of the earliest artist guilds. First members were primarily manuscript illuminators; however, over time, the membership varied to include scribes, visual artists, sculptors, art dealers, art patrons, painters and decorators. The guild exercised considerable power through its regulations of apprentice training and art sales. It also mediated disputes between artists or artist and their clients.

Upon completion of three to five year apprenticeships, an artist became a journeyman and free to work for any guild member. However, it was not until they became free masters that they could set up their own shops, apprentice young artists, and sell their work and the work of others. Guilds usually excluded women from membership and from becoming free masters. Two notable exceptions to this practice were Caterina van Hemessen who joined the famous Guild of Saint Luke in Antwerp and Judith Leyster who was a member of the guild in Haarlem.

In the 17th century, the guilds began to decline. This was due to the movement toward academy style education which separated training from the actual sale of art. Another factor was the tension which developed between guild members and artists who served specific monarchs. Very few guilds survived to the end of the 18th century.

In the 17th century, the guilds began to decline. This was due to the movement toward academy style education which separated training from the actual sale of art. Another factor was the tension which developed between the men who were guild members and the male artists who served specific monarchs. Very few of those guilds survived to the end of the 18th century.

But the contribution of women to the world of art was far from over with the demise of the guilds. They would re-emerge over the following centuries, women's influence and work waxing and waning, their innovations sometimes appropriated by men. In the twentieth century things began to change for female artists which mirrored the slow progress toward equality and power in Western Society. This includes, for example, the first wave of feminism in the late 19th Century which centered on a woman's right to vote. (The US Congress did not grant suffrage until 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment.)

Girl at a spinet (self-portrait?), Caterina van Hemessen. 1548. Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne. Self-portrait. Caterina van Hemessen. 1548. Öffentliche Kunstsammlung, Basel.

Caterina Van Hemessen trained with her father, an accomplished artist. She enjoyed considerable success, becoming one of the few female artists in the Guild of Saint Luke and subsequently secured the patronage of Queen Mary of Hungary. The self-portrait of Caterina Van Hemessen (right) is the earliest known example of an artist seated at an easel. The other painting of a young woman playing a spinet is earlier and may be either Caterina or her sister. If it is Caterina, then the painting is the oldest surviving self-portrait of an artist at work.

In 1554, Van Hemessen married Chrétien de Morien, the organist of Antwerp Cathedral. There is no later artwork that can be identified as hers, leading art historians to speculate that she stopped painting after she married. In 1556 Queen Mary resigned her regency and invited Van Hemessen and her husband to join her in Spain. The couple lived there until Queen Mary's death in 1558. In appreciation for their loyalty, the queen bequeathed them funds sufficient to live the remainder of their lives in comfort.