LIFE AS MYTH

![]()

JOURNAL

![]()

JOURNAL 2011

![]()

Life as Myth

Naming a life

![]()

SUMMER 2011

A feminine myth

![]()

LIFEWORKS

![]()

ATLAS

![]()

SUMMER 2011

THE MANET MYSTERY

Berthe Morisot with a bouquet of violets [detail]. Édouard Manet. 1872. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. When Manet painted this portrat, Morisot was in mourning following the death of her father. [below left] A bouquet of violets. Édouard Manet. 1872. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

You would hardly believe how difficult it is to place a figure alone on a canvas, and to concentrate all the interest on this single and universal figure and still keep it living and real.

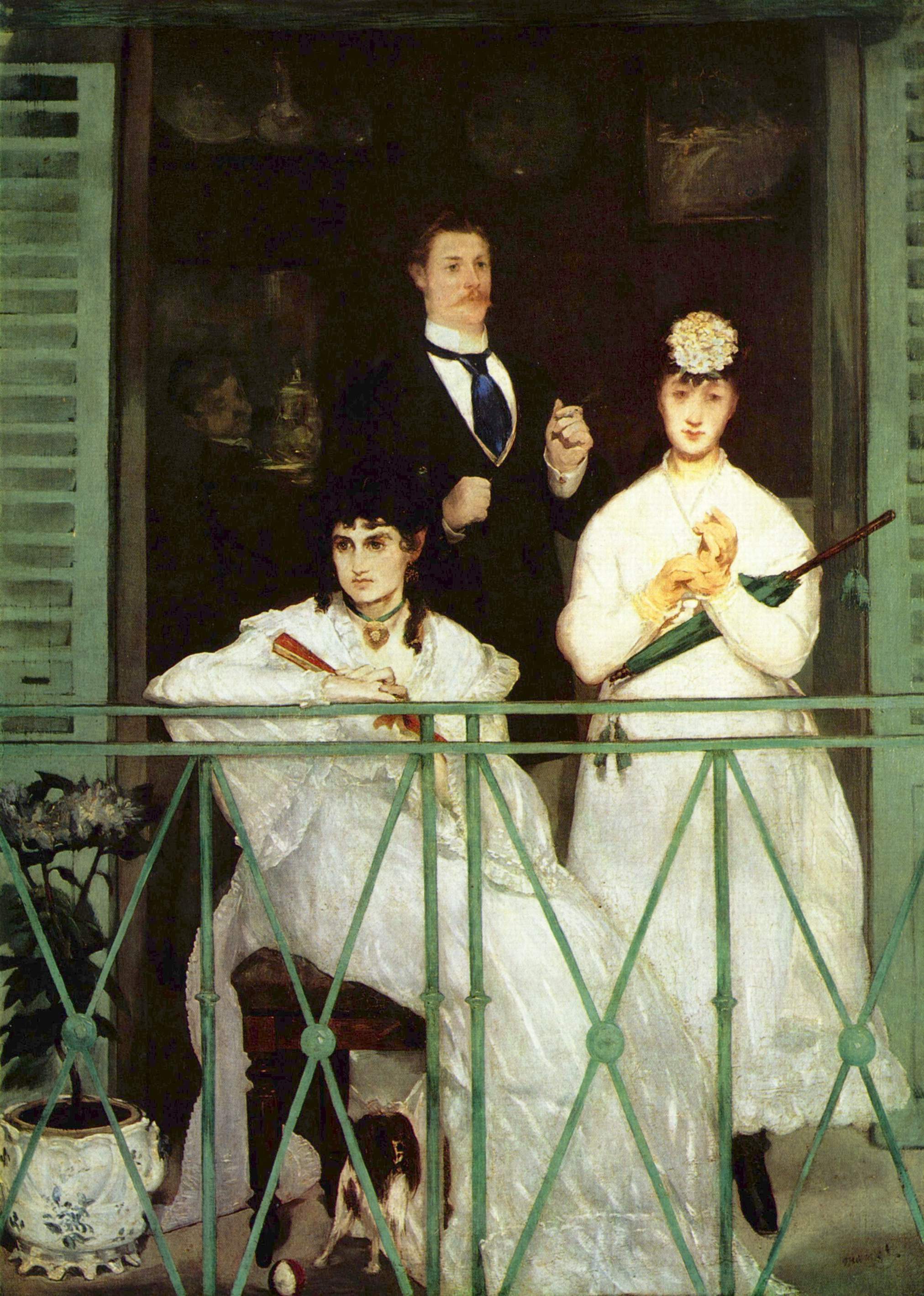

Édouard Manet (1841-83)By all accounts, Berthe Morisot fascinated the married Édouard Manet. Between 1868, when they first met, and 1874, when she married his brother, he painted her portrait eleven times, making her his most frequent model. His wife Susan Leenhoff sat for five paintings [Luncheon on the Grass] and Victorine Meurent [Olympia, Luncheon on the Grass], eight.

The exact nature of their alliance is unclear and continues to intrigue art historians. It is known that he helped her develop her style. Additionally, he introduced her to his brother Eugene whom she later married. Morisot, on the other hand, encouraged Manet to abandon the use of black and to utilize the brighter palette characteristic of the Impressionists. She also influenced him to practice plein-air painting.

Manet produced his final images of Morisot during the time she became involved with his younger brother and then married him (1872-74). These last portraits provide a window into the intense desire and rivalry which Manet felt in his relationship with her. As the loss of Morisot neared, there was an increasing distortion of her image and departure from his usual painterly technique. This culminates in the skull-like portrait Berthe Morisot in a mourning hat [1874]. After Morisot's marriage, Manet never painted her again.

His painting, A bouquet of violets, which Manet gave to Morisot in 1872, is another intriguing dimension to their relationship. The violets and fan are objects found in two earlier portraits: The Balcony, where she carries a red fan, and Berthe Morisot with a bouquet of violets, where the violets are pinned to her dress. The third object, a partially folded letter, reveals handwriting which reads: à Mlle Berthe and bears the signature, E. Manet. Art historians note that this particular trio of symbols represents the primary tools of Victorian seduction. In other words, the painting serves as Manet's coded communication of sexual desire.

(clockwise) The Balcony. Edouard Maney. 1868. Musee d'Orsay. Paris. This is the first painting in which Berthe Morisot sat for Manet. The other three people in the composition [not picture in this detail] are Antoine Guillemet, a landscape painter; Fanny Claus, a violinist; and, in the shadows of the background, his son Leon Leenhoff.

Berthe Morisot with a veil. Édouard Manet. 1872. Musée du Petit Palais, Geneva.

Berthe Morisot with a fan. Musée d'Orsay. Paris.