LIFE AS MYTH

![]()

JOURNAL

![]()

JOURNAL 2015

1001 stories

The gift of self

![]()

SUMMER 2015

Navigating dark waters

![]()

LIFEWORKS

![]()

ATLAS

![]()

SUMMER 2015

NAVIGATING DARK WATERS

Orpheus. Odilon Redon. 1905. The Munch Museum. Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

First, a story.

Orpheus (meaning the darkness of night) was a poet whose music was so enchanting that he could charm all creation when he sang and played his lyre. Eurydice (meaning wide justice) was an oak nymph and the daughter of the sun-god Apollo.

Eurydice and Orpheus fell deeply in love. On their wedding day, Eurydice danced across a meadow while Orpheus played on his lyre. During the dance, a viper bit her heel and she died. The loss of his bride was so profound that Orpheus descended into the underworld to beg the gods to release her, petitioning Hades and Persephone through song. His music was extremely sorrowful, the story says, bringing tears to the eyes of the gods.

Hades agreed to return Eurydice to Orpheus on one condition: she must walk behind her husband for the entire journey out of the underworld and Orpheus must not look on her face until they had both exited. Despite the warning, just as they neared the surface, Orpheus turned around to make sure that Eurydice was still following him. When he turned, she vanished and Orpheus returned to the land of the living alone.

Why? That's the philosophical question. Why did he turn? Didn't he know what would happen? The most common explanation was that he loved her so completely that he could not risk returning to the world without her. He had to know she was still there, that she was following him. In other words, his heart overruled his reason and he turned to check even though, in doing so, he lost her forever.

That explanation aligns with a traditional narrative structure, one that is deeply embedded in our world. Classical storytelling focuses on male individuation and conquest, and identifies women as trophies, the ultimate reward of the hero. However, I think there could be something far more interesting going on in this particular myth, if we bring a little Zen to it. And a little bit of Rilke.

That was the deep uncanny mine of souls, writes Rainer Maria Rilke as he opens "Orpheus, Eurydice and Hermes," a poem based on this myth. With Rilke and through his poem, we descend into the land of the dead, arriving at the intersection he creates between the death of an old myth and the birth of a new one. That intersection is the point where Eurydice and Orpheus see each other. It is not just that Rilke reimagines the myth of Eurydice and Orpheus, he also radically reimagines the meaning of their parting.

At her death, Eurydice, no longer the bride of Orpheus, becomes instead his muse. Consider. After her death she inspires music of such exquisite beauty that all creation stills to listen and the gods weep. In other words, her absence provides access to greater creative depths than Orpheus had heretofore achieved on his own.

Eurydice, as Rilke describes her, has gone through an irreversible transformation, one that was taking her to an existence far richer than the one she ever knew with Orpheus. The poet writes,

She was no longer that woman with blue eyes

who once had echoed through the poet’s songs,

no longer the wide couch’s scent and island,

and that man’s property no longer.

She was already loosened like long hair,

poured out like fallen rain,

shared like a limitless supply.

She was already root.Eurydice had reached the source. She was no longer able to follow behind and in her husband's footsteps. She was whole; she was subject.

Why? We return to the philosophical question. Why did Orpheus turn? Didn't he know what would happen? I believe that Rilke answers yes -- on some level, Orpheus knew the result of violating the prohibition against looking and that is what he chose. He wanted to lose her. The only way that could happen was to break the one condition that Hades made. I believe that Hades gave Orpheus a choice, already understanding the transformation in Eurydice and knowing in advance how Orpheus would choose.

Eurydice was now subject and Orpheus, as artist, needed her to remain object, muse, forever a reflection of his desire, never subject, never root.

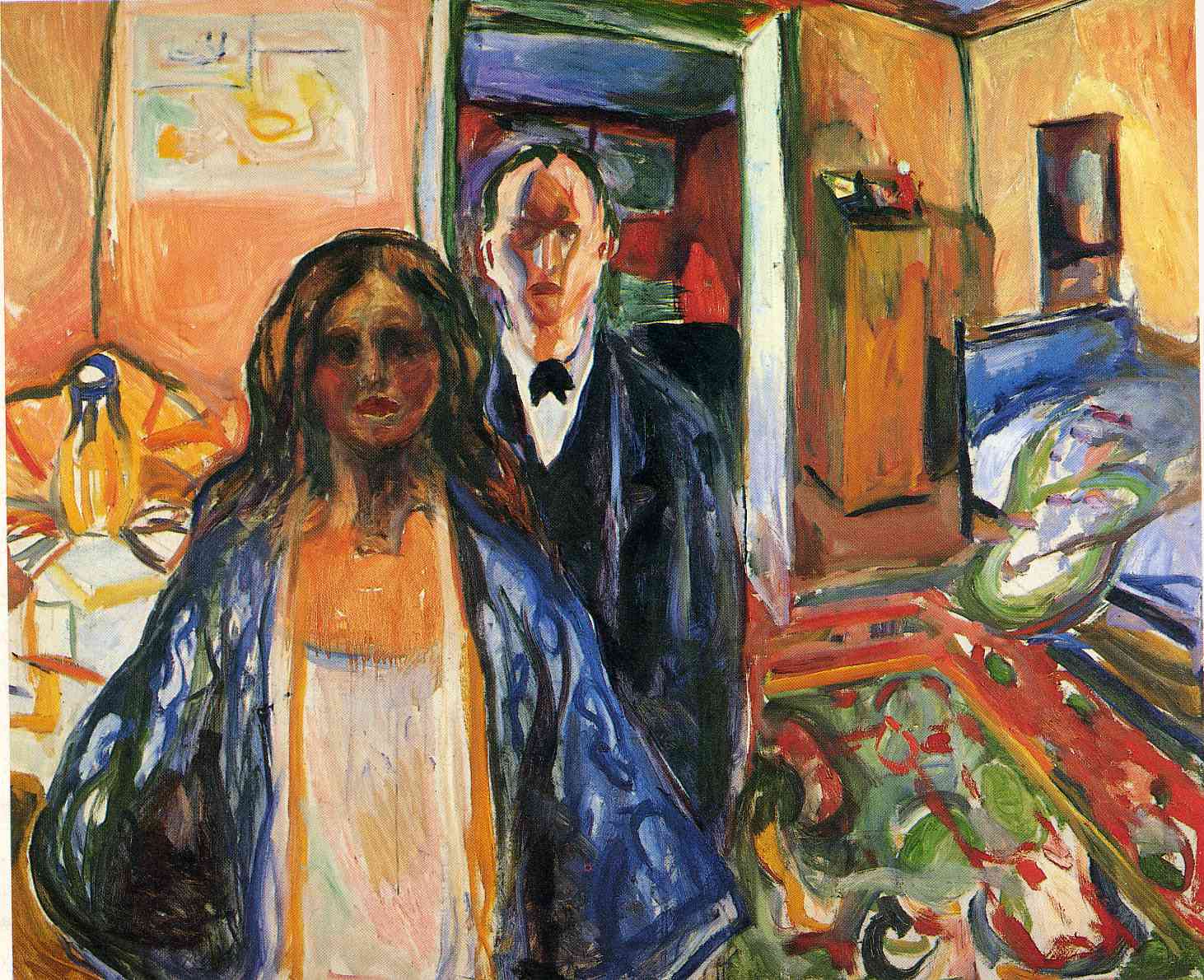

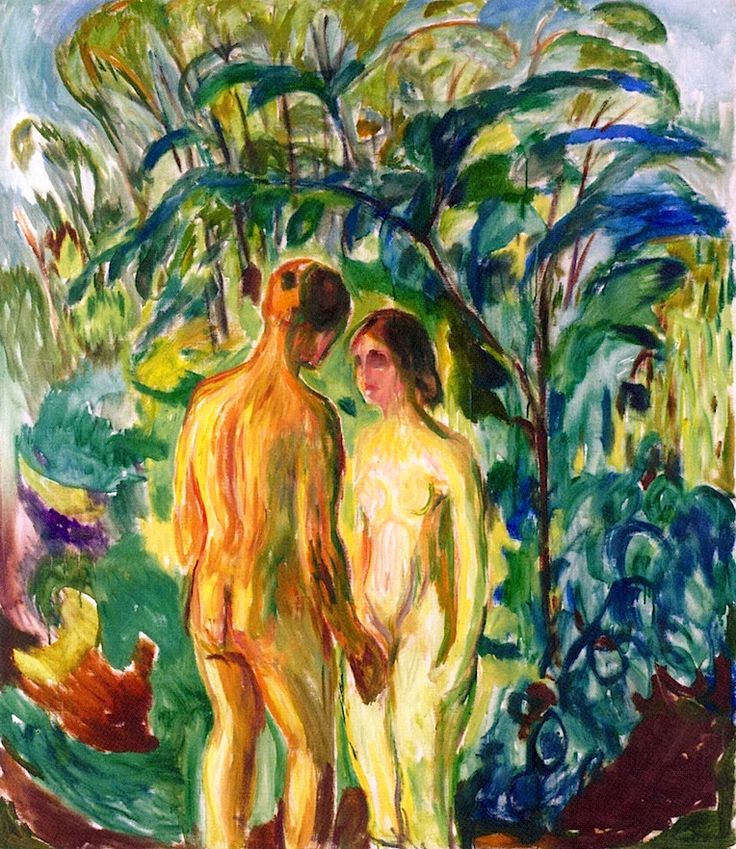

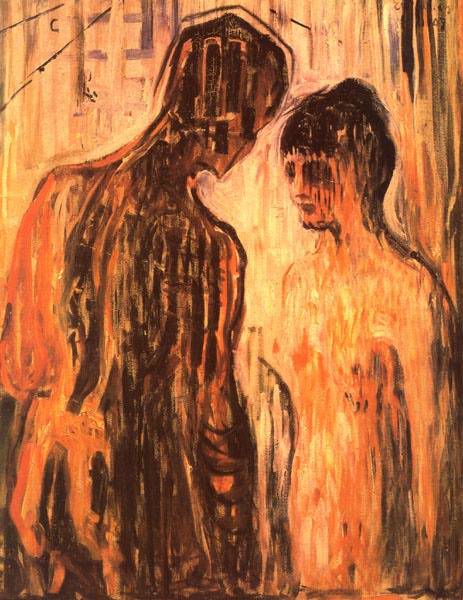

(clockwise) The artist and his model.Edvard Munch. 1921. Naked man and woman in the woods. Munch. 1919-25. Psyche and Cupid. Munch. 1907. The Munch Museum. Oslo, Norway.

Edvard Munch was the second child born to Christian and Laura Cathrine Munch. Munch's mother died of tuberculosis in 1868 and his favorite sister, Johanne Sophie, also died from the disease in 1877. After his mother's death, Christian raised the children in an atmosphere of religious fear, frequently instructing them that if they sinned in any way, they would go to hell without hope of pardon. Munch's younger sister was diagnosed with mental illness at a very young age. Munch himself was also often quite ill. The only one of the five siblings to marry, his brother Andreas, died a few months after the wedding. His father died at an early age as well (1889).

Throughout his life, Munch used his art to come to terms with the death and illness which filled his childhood. The Scream (1893), his best known painting, is characteristic of his early work.

In 1908, suffering from acute anxiety, he received psychiatric treatment and electroshock therapy at the clinic of Dr. Daniel Jacobson. The psychiatric treatment dramatically altered Munch and his work. Around 1909, the artist began to give voice to this change, depicting the healthcare staff and environment along with a new perception of self through vibrant colors and harmonious forms. Returning to Norway after treatment, he revisited old themes of death and loss in his work but Munch's recapitulation also incorporated the changed approach to art, the canvases of the artist now reflecting a transformed interior state. This tension between new approaches and old losses never resolved fully, continuing to emerge in his painting and self-portraiture until the end of his life.

The separation. Edvard Munch. 1896. The Munch Museum. Oslo, Norway. This is one in a series of paintings that expressed the artist's on-going struggle to reconcile the loss of a woman he loved.